“Vienna, Berlin, and St. Petersburg, are forced cities, built under the iron rule of despotism, to decay, doubtlessly, upon the overthrow of arbitrary power.”

“Vienna, Berlin, and St. Petersburg, are forced cities, built under the iron rule of despotism, to decay, doubtlessly, upon the overthrow of arbitrary power.”

(S.H. Goodin, “Cincinnati – Its Destiny”, Sketches and statistics of Cincinnati in 1851;: Charles Cist, 1851).

To S.H. Goodin, one of the “boosters” promoting the development of the west in the early 19th century, the most successful cities were those with the most “gravity”. In this instance he is writing about Cincinnati, a city that did not become the “grand centre” of the United States. In Goodin’s world, cities are natural entities competing and struggling for “supreme ascendency”. Many claiming to understand physics and biology in the 19th century tried their best to apply supposedly natural laws to human forces, typically as a means of justification. After all who can deny science? But a city is a man-made object. The idea of a city is itself man-made. The apparent complexity of cities today often overshadows the fact that the urban landscape has been shaped by man and not invisible, mystical forces. Naturalistic thinking like Goodin’s in the 19th century justified and promoted the expansion of cities, which many inside players profited from. He and other boosters invented a seemingly rational, though inconsistent, set of laws for city development, which just happened to work perfectly for the settling of the blank American frontier, an apparent tabula rasa for a new world.

In Europe, however, where cities have had a major presence for millenia, the formula is much more difficult to apply. Goodin’s annoyance with European cities like Berlin and St. Petersburg is that they represent centralized power. These “forced” cities were in fact built in swamps; the only natural advantage of their locations is their nearness to waterways. Berlin was built on a meager river and indeed remained a rather small city up until its establishment as Prussian capital in the 18th century and eventually capital of the German Kaiserreich in the 19th century. Berlin does not try to hide its foundation as a city built on sheer power and prestige. The Prussians envisioned a grand city and that’s what they built, there’s nothing natural about it. The 17th century onward would prove to be an era of major players shaping cities in a top-down fashion across the western world. As power came to be consolidated under centralized governments and absolutist monarchies and the new moneyed elite, the city came under the mercy of their control through the forced taking of common land and privitization. Americans often chafe under this notion, but similar forces were acting in the newly formed United States as well. While the frontier did provide the opportunity once again for individual families to own their own land, it was first transacted between the government and businessmen in the east and surveyed under their own determination to ease the transformation of land into a commodity to be sold for profit. Therefore, every potential site for a new city in the frontier was trying to position itself as the future center of the new power dynamics under capitalist commerce.

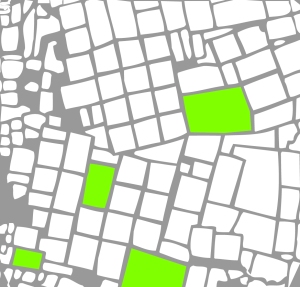

Berlin exemplifies the city as a product of layers of different forces and intentions through time and is clearly apparent in its physical form. Its special status as capital city may have bloated the city out of proportion to its economic value in an industrial-capitalist sense, as its current form is the product of prestige projects by ruling elite. Indeed, once the economic conditions changed after the Cold War the city initially found itself in a rough position, and the turmoil of constant renewal projects has ignited protest movements throughout its troubled history. But its multifaceted nature may actually help the city in the long run to overcome issues related to housing, green space, and transportation. The city was in a sense “over-built” but in the same way that Manhattan was over-planned: Manhattan’s grid was anticipating a prestigious future of commerce and real estate. Germany’s royalty and various rulers envisaged and built Berlin as a prestigious capital city, whose plentiful green spaces, large housing projects, and extensive infrastructure may be help to relieve future growth spurts if preserved and maintained. And its stagnant economic situation has not slowed the current influx of population and immigrants.

Phil Fargason’s contributing essay provides an indepth look at the history of Berlin since the Cold War and its current state. This is part 1 of 2.

A City in Search of Prestige (Part 1)

By Phil Fargason

Berlin, Germany has been at the center of many of the past century’s most intense global conflicts. A fraction of Berlin’s 3.5 million current residents saw first-hand the atrocities of the Third Reich, lived on edge as the city rebuilt along dividing lines during the Cold War, and struggled to adapt as their city sought global city status after reunification. Berlin is an exceptional city in which to study the sometimes effective and often counterproductive efforts of empowered urban planners faced with grave challenges.

Berlin is an interesting case study in a city’s response to trauma. Devastated economically by the First World War, then over halfway destroyed by the Second World War, Berlin has been in a near constant housing shortage for most of the last century. (Urban, 2009) The city’s economy has also faced difficulty in recovering from wartime destruction and Cold War isolation.

As the German capital, Berlin has long aspired to greatness. Berlin’s planners and politicians have wielded large powers in order to implement their vision of greatness on the urban landscape. In the 18th Century, Berlin was the capital of the sprawling Prussian Empire, and massive building projects such as the Brandenburg Gate were meant to symbolize the power of this regime. In each subsequent period of political change and reconstruction, Berlin’s government has pursued similar building projects—often involving removal and clearance—in order to display the greatness of a world-class capital city. Hitler’s “first architect”, Albert Speer proposed sweeping renewal projects for Berlin during the brief reign of the Third Reich. East and West German governments competed to display the superiority of their economic models through renewal projects during the Cold War. After the city was reunified in 1990, Berlin’s government continued this tradition of renewal and mega-projects.

The focus of Berlin’s planners and politicians on prestige has produced a form of trauma of its own. During the Cold War, subsidies for manufacturing firms kept the divided city afloat, but also set Berlin up for a sharp decline as the economy was restructured in the 1990’s. With reunification, planners generated overly-optimistic population and growth projections, pushing through grandiose, often failed public projects, which left the city on the verge of bankruptcy for most of the 21st century. Berlin’s grand development plans have come at the expense of its basic municipal responsibilities: providing affordable housing and public services to its constituents. As a result, the city’s most disadvantaged citizens have often been displaced from their homes and left jobless. Berlin’s residents have fought back against these failures, inciting protests which coalesce into social movements. These movements have had an impressive ability to affect policy changes.

The focus of Berlin’s planners and politicians on prestige has produced a form of trauma of its own. During the Cold War, subsidies for manufacturing firms kept the divided city afloat, but also set Berlin up for a sharp decline as the economy was restructured in the 1990’s. With reunification, planners generated overly-optimistic population and growth projections, pushing through grandiose, often failed public projects, which left the city on the verge of bankruptcy for most of the 21st century. Berlin’s grand development plans have come at the expense of its basic municipal responsibilities: providing affordable housing and public services to its constituents. As a result, the city’s most disadvantaged citizens have often been displaced from their homes and left jobless. Berlin’s residents have fought back against these failures, inciting protests which coalesce into social movements. These movements have had an impressive ability to affect policy changes.

In this essay, I have studied Berlin’s recent growth trajectory, its record on human development, the political process informing development trends, and the city’s common resources.

Berlin’s Growth Trends: Disappointing Growth and Speculative Building

Historically, the economic powerhouse of Prussia and pre WWII Germany, Berlin’s population and economy have been largely stagnant since 1950. (Das Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg) The city’s economic survival from the end of WWII through reunification is the result of large subsidies granted by the German federal government. These subsidies allowed Berlin to retain its population throughout the Cold War, even as the city became unattractive to investors, and provide a decent quality of life for its citizens. (Strom, 2001) Since reunification, Berlin’s manufacturing sector has declined sharply as federal subsidies have been removed, leading to a high level of unemployment. Meanwhile, Berlin’s service and professional sectors have failed to grow at the rates that planners had projected since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Berlin’s government, which invested heavily in a speculative office building boom in the early 1990’s which never occurred, reached a state of near bankruptcy by 2000. (Hooper, 2001) Though Berlin’s long trend of population loss was finally reversed in 2011, the scars from the city’s post-reunification period of speculative growth remain. The municipal government’s aggressive attempts to stimulate and prepare for growth over the post-reunification period hindered Berlin’s long-term success: leading to an over-supply of office and residential space, fragmented suburban sprawl, mistrust among residents, and municipal insolvency.

Pains of Economic Restructuring

In order to maintain West Berlin as a capitalist oasis, surrounded on all sides by the hostile German Democratic Republic (GDR or East Germany), the West German federal government subsidized over 50% of Berlin’s municipal budget during the Cold War . (Strom, 2001) Shortly after the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the federal government reduced the sales tax for any good produced in West Berlin and provided grants and improved depreciation terms to encourage capital investments. German companies oriented themselves in order to take advantage of these incentives during the Cold War period, investing in manufacturing plants in West Berlin which would sell their goods elsewhere in Germany. (Strom, 2001) The incentives did not provide any benefits for service sector firms, which require less physical space and do not produce taxable physical goods. Thus while other German cities began restructuring their economies from manufacturing to service industries, Berlin remained hitched to a “falling star.” (Strom, 2001) The subsidies even resulted in a qualitatively different economy in Berlin, one that Strom referred to as “decidedly unentrepreneurial.” (p.82)

After reunification and the removal of key industrial subsidies, Berlin’s manufacturing sector suffered a 41% decline over 8 years (a loss of over 200,000 jobs), while public sector jobs declined by a similar figure as Eastern and Western Bureaucracies were consolidated. The service sector grew to absorb only a portion of these losses, adding only 100,000 jobs by 1997. As a result, Berlin’s population declined after reunification, and unemployment rose sharply to over 17%. (“Berlin: Towards an integrated strategy, 2003)

Since reaching this peak unemployment, jobless levels in Berlin have dropped slightly, reaching 11.7% in 2014, and since 2011 the population has increased. Recent population gains of 1.4% per year indicate that Berlin’s service sector may slowly be making up for the jobs lost in Berlin’s industrial collapse after reunification. (Das Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg)

Suburban Expansion

Berlin’s reunification optimism also led the city to conduct large residential housing estates—over 100,000 new units of housing—along the city’s urban fringe (Bernt, 2013). Most of these “New Suburbs” were publically financed, multifamily developments just within the city limits of Berlin. This new construction led to an oversupply of housing and an additional fiscal burden for Berlin’s struggling government.

Publicly financed suburban development is nothing new for Berlin. After WWII, both East and West Berlin had to replace the large number of housing units destroyed in the war. Both governments selected to construct high-rise housing towers in decentralized areas along Berlin’s suburban fringe. For political reasons, all Cold War suburban development was forced to remain within the city limits of Berlin, which is itself a sizable area (344 square miles.) West Berlin’s growth was physically constrained by the hostile boundary with communist Brandenburg, while GDR policies promoted density. (Bachmann, 2007) These housing developments were relatively accessible to transit and job centers because Berlin’s industry and commercial centers are decentralized, with multiple medium-density nodes. (Jeschke, 1999) In the absence of private financing, nearly 50% of all housing constructed in Berlin until the 1980’s was either publicly financed or subsidized and thus had rent control limits. (Strom, 2001)

The reunified government continued to build thousands of units of social housing into the late 90’s. The government rushed to supply housing for the expected new population of 1.4 million people, who were expected to come as immigrants from Eastern European and the rest of Germany. (Bodnar, 2010) The government selected green-field and brownfield sites along the fringe of the city-limits for a series of “mega-projects” such as the 5,100 dwelling Karow-Nord development on the Eastern fringe. Throughout the early 1990’s these multi-family state-subsidized housing projects made up over 70% of new residential development. (Bodnar, 2010)

In 1998, state housing subsidies were abruptly halted due to budget shortfalls. Private industry largely replaced the state system of suburban development, choosing sprawl and fragmentation as its primary typology. Since 2000, Berlin’s suburban development has changed dramatically from multi-family housing within city limits to privately financed single-family homes, built by small developers in the surrounding state of Brandenburg. These new developments are typically built at low densities for the most wealthy of Berlin’s residents. (Bodnar, 2010)

The 2000’s: Privatization and Modest Growth

By the late 1990’s the consequences of the Berlin government’s counterproductive development strategies could be clearly seen. After the reunification construction euphoria wore off, Berlin’s government faced a massive budget shortfall as incentives for downtown office developments failed to pay off and suburban housing estates suffered high vacancy rates. As debts worsened and federal reunification supports dwindled, Berlin was forced to sell nearly half of its publicly owned social housing and privatize many of its other assets including its water supply in the early 2000’s.

Throughout the 2000’s, Berlin’s economy slowly recovered. By 2011, Berlin’s population began to grown modestly by 1.4% per year. This is largely the result of increased migration from Turkey and Poland as the economy has slowly improved. The health care and social work sectors; real estate professional, scientific and technical service sectors all grew during this time along with the expansion of the federal government. (Das Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg) The weak and indebted local government, however, has not been able to ensure that this recent growth has occurred in an equitable fashion. The housing oversupply that existed in the 90’s has become a shortage, leading to rapidly rising rents in Berlin’s accessible and desirable neighborhoods. Immigrant populations which continue to face double-digit unemployment have been increasingly displaced from their homes.

Slow Growth Leads to Poor Opportunities

Not surprisingly, the stagnation of Berlin’s economy has negatively affected the well-being of Berlin’s population. While Germany’s quality of life is higher than that of the most of the world, East Germany has lagged behind the rest of the country in many key indicators including income and employment opportunities. (Noak, 2014) The people of East Germany have shown their sensitivity to this lack of opportunity, choosing to leave former GDR states at the rate of 1-2% per year since reunification. Berlin suffers from these same ailments. Even with modest growth, unemployment as of 2013 was still 11%. While this unemployment is suffered most severely among new immigrants with low education attainment, unemployment is high even among Berlin’s large number of college educated residents. (Das Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg)

As the service economy slowly grows, unemployment among educated professionals will decline, while immigrants may continue to struggle to find work and housing. The failure of the public sector to preserve the city’s stock of affordable and social housing throughout the 2000’s ensures that as Berlin’s economy and population finally begins to grow, disparities will also grow with them.

‘Poor but Sexy’ Fails Even the Creative Class

Berlin’s poor economic growth since reunification has ensured that even the so called “creative class” has suffered high unemployment levels. This confounds the theories of writers such as Richard Florida who propose that urban areas that are tolerant, livable, have technological infrastructure and concentrations of well-educated young people will be likely to attract firms to their cities to produce economic success. (Florida, 2002) Since 1990, however, Berlin’s economy has failed to grow despite its urban amenities and top universities which attract numerous young people to the city. In the words of Berlin’s former mayor, Klaus Wowereit, Berlin is “Poor but Sexy.” As Enrico Moretti describes, Berlin’s sexiness, has surprisingly failed to attract job growth:

Thousands of young, college-educated Italians, Spaniards, and French men and women move [to Berlin] every year, attracted by its world-class cultural landscape, its countless galleries and incredible public art displays, its unparalleled mix of highbrow and alternative music offerings, its edgy dance clubs that are open no earlier than 1 A.M. […] Berlin also has one of Europe’s most affordable housing markets; government subsidized, high-quality childcare; good schools; and outstanding public infrastructure […] But after twenty years of Berlin coolness, the supply of well-educated creatives vastly exceeds demand. (Moretti, 2012, p. 191-2)

Moretti suggests that for cities to grow, they have to attract jobs, not just talented people. Attracting jobs, however, is challenging, given the competition between cities to provide broad incentives to lure businesses to their area. Berlin’s resources would be better employed in ensuring broader opportunities to immigrant groups, who are less able to access Berlin’s employment in the city’s (albeit slowly) growing service sector.

Challenges for Immigrants in West Berlin

After reunification, the former East Berlin has fared better than its Western counterpart, retaining a steady population and lower poverty levels than the West. The disparities between the two sections of the city is because immigrants have settled disproportionately in the Western portion of the city, where they are living in increasingly ghettoized conditions. (Mayer, 2006) Immigrant households, which currently compose 16% of the population in Berlin are more likely to face unemployment, and three times more likely to be impoverished than native Germans, due to their inability to access service-sector jobs. (“Berlin: Towards an integrated strategy, 2003) Immigrant families also have proven to have difficulty accessing higher education. “The competitive environment limits access of Berliners with immigrant backgrounds to higher education as they usually lack the secondary schooling grade levels that would ensure entry into the system.” (“Berlin: Towards an integrated strategy, 2003)

Berlin has a long history of immigration. Labor shortages at the end of World War II led to the need for immigration arrangements with neighboring countries. In the 1950’s Germany engaged in a number of agreements with neighbors allowing for temporary visas for “guest workers” who would support German industry. Berlin attracted a large population of immigrants from Turkey, Poland, and the former Yugoslavia along with smaller numbers from a wide range of European, African, and Asian countries. (Seidel, 2015)

Following the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, West Germany made a push to allow for increased temporary immigration to stem West Berlin’s population loss and keep manufacturing plants in Berlin running. Immigration to East Berlin during this time was minimal. This widespread immigration to West Berlin continued until 1973 when the worldwide oil crisis led Germany to terminate the guest worker program. Many of the temporary workers who had made a home in the country were allowed to remain, but as the manufacturing jobs fled Berlin after reunification, these immigrants bore a disproportionate share of the rising unemployment.

Berlin has seen ever changing tides in approaches towards addressing the immigrant community, alternating between a removal and dispersal strategy popular during the renewal era towards a more sensitive integration and support strategy. Ever since the beginning of the guest workers program, portions of the native Germans community in West Berlin, have looked negatively upon immigrant communities which tended to cluster together in units of mutual support in the center city. During the period of popular urban renewal and rapid influx of immigrants in West Berlin in the 60’s and early 70’s, immigrant neighborhoods were systematically derided by mainstream media as unsafe and unseemly. (Mayer, 2006). The city used renewal policies in the post-war period to clear these communities from desirable downtown until renewal policies were met with widespread squatter uprisings in the 80’s.

Following the student and squatters uprisings between the 70’s and 80’s raised social consciousness in Berlin, the City turned to policies emphasizing integration and support for immigrants, mirroring Germany’s new pro-immigration policies. (Lanz, 2011) These policies are intended to “mitigate the worst effect of restructuring and exclusion,” though in Berlin, these policies have done little to help immigrants in Berlin to adjust to a service-based economy, change their poverty status, or helped them to avoid displacement from attractive downtown areas. (Mayer, 2006). Given the growing refugee crisis in Europe and Africa, the plight of immigrants in Berlin is likely to worsen unless dramatic policy action is taken.

Loss of Affordable Housing and Gentrification

A recent trend towards population growth in Berlin has spurred a glut of new construction in the most desirable districts of the city, sparking protests and bringing the issue of gentrification and tenure to the fore. Throughout the 90’s Berlin saw the growth of “Insular gentrification” of select downtown areas by younger, non-family, well-educated households. (Mayer, 100) Despite these small changes, rental rates remained the same in Berlin between 1990 and 2005, the result of an oversupply of housing following reunification, a large publicly held social housing portfolio, and rent regulations. This lead to a housing system that was “much less vulnerable to market dynamics. (Holm, 2013, p. 178)

In the early 2000’s, however, Berlin’s government turned towards privatization of public resources and the removal of rent regulations. Faced with ballooning municipal debt for its post-reunification building projects, the city’s liberal leadership took steps to balance the budget through austerity measures, privatized a number of municipal services including its water supply, and reduced funding and wage cuts for schools, hospitals, municipal government. (Bernt, 2013)

Berlin stopped all new building of social housing and sold over half of its social housing portfolio, largely to private investors. Investors who purchased these assets chose to either add value through upgrades which allowed them to raise rents or hold the buildings in a minimally maintained level until a favorable buyer would come along. (Uffer, 2013) Each of these strategies had negative effects on quality of life for Berlin’s unemployed and immigrant populations.

Rents rose by a dramatic 23% between 2003 and 2013 across the city, with a steeper rise in central city neighborhoods. (Holm, 2013) In the downtown districts such as Mitte, the city conducted “politically-initiated gentrification” which led to the widespread renovation of existing buildings as luxury housing. In other areas, such as Kreuzberg, the renovations have been done under the “careful urban renewal” strategy, which establishes a rent cap for a period of time after incentivized renovation occurs. But even for these more careful renewal efforts, as public subsidy periods expire existing residents, particularly immigrants, are displaced. (Holm, 2013)

In recent years, Berlin’s renters have organized widespread protests in response to gentrification, which have won them legal protections against rapid rent increases and abuses from landowners. These protest movements follow in Berlin’s long tradition of activism against the abuses of urban renewal planners and the city’s political growth machines.

Bibliography

Bodnar J. and Molnar V. (2010) “Reconfiguring public and private: Capital, state and new housing developments in Berlin and Budapest”. Urban Studies. 47(2): 789–812.

Bachmann, M. (2007). Berlin-Adlershof: Local Steps Into Global Networks. In Salet, W. (2007). Framing strategic urban projects: Learning from current experiences in European urban regions. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Bernt, M. (2013). The Berliner reader: A compendium on urban change and activism. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Berlin U-Bahn Upgrading. (n.d.). Retrieved November 6, 2015. http://www.railway-technology.com/projects/berlin-u-bahn-upgrade/

Berlin: Towards an integrated strategy for social cohesion and economic development. (2003). Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Das Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg, Retrieved November 6, 2015. https://www.statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de/

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Hammer, J. (2015, July 23). How Berlin’s Futuristic Airport Became a $6 Billion Embarrassment. Retrieved November 6, 2015. Bloomberg News

Hansen, Rieke. (2015) Berlin, Germany: Case Study City Portrait. TUM. 1.0 http://(Hansen, 2015) .eu/products/case-studies/Case_Study_Portrait_Berlin.pdf

Hooper, J. (2001, May 1). Barnkrupt Berlin turns off Fountains. The Guardian.

Holm, A. & Armin Kühn, (2011) “Squatting and Urban Renewal: The Interaction of Squatter Movements and Strategies of Urban Restructuring in Berlin: IN International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 35.3, 644–58

Holm, A. Berlin’s Gentrification Mainstream IN Bernt, M. (2013). The Berliner reader: A compendium on urban change and activism. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. 171-188.

“In gritty Berlin, green space plays a surprisingly large role” | Culture | DW.COM | 12.04.2011. (n.d.). Retrieved November 6, 2015. http://www.dw.com/en/in-gritty-berlin-green-space-plays-a-surprisingly-large-role/a-14983881

Jeschke, C. (1999). Metropolis on the Move-Public Transport in Berlin. Japan Railway & Transport Reviow, 20.

Klemek, C. (2011). The transatlantic collapse of urban renewal: Postwar urbanism from New York to Berlin. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Krätke, S. (2004). City of Talents? Berlin’s Regional Economy, Socio-spatial Fabirc and “Worst Practice” Urban Governance. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28.3, 511-529. IN Bernt, M. (2013). The Berliner reader: A compendium on urban change and activism. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Lanz, S. (2011) Berliner Diversitaten: Das Immerwahrende Werden einer whrhaftigen Metropole. IN Bernt, M. (2013). The Berliner reader: A compendium on urban change and activism. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Mayer, M. (2006) New Lines of Division in the New Berlin. In Lenz, G. et al. (eds.) Towards a New Metropolitanism: Reconstituting Public Culture, Urban Citizenship and The Multicultural Imaginerin in New Yourk and Berlin. Universitatsverlag Winter, Heidelberg, 171-183. IN Bernt, M. (2013). The Berliner reader: A compendium on urban change and activism. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Müller, P. (2005) Counter-Architecture and Building Race: Cold War Politics and the Two Berlins. GHI BULLETIN SUPPLEMENT: 2 (2005)

Noak, R. (2014, October 1). The Berlin Wall fell 25 years ago, but Germany is still divided. Retrieved November 6, 2015. Washington Post.

Berlin-A Thriving City Embraces its Green Spaces. (n.d.). Retrieved November 6, 2015.http://cbc.iclei.org/Content/Docs/02-URBES-pb%20Berlin%20III%202%20Feb.pdf

O’Sullivan, F. (2015). Berlin’s New Rent Control Laws Are Already Working. Retrieved November 6, 2015. http://www.citylab.com/housing/2015/07/berlins-brand-new-rent-control-laws-are-already-working/398087/

Seidel, Eberhard, (n.d.) Migration to Berlin. Berlin.de. Retrieved November 6, 2015. (https://www.berlin.de/lb/intmig/migration/index.en.html)

Strom, E. (2001). Building the new Berlin: The politics of urban development in Germany’s capital city. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books

Uffer, S. (2013) The Uneven Development of Berlin’s Housing Provision: Institutional Investments and Its Consequences on the City and its Tenants IN Bernt, M. (2013). The Berliner reader: A compendium on urban change and activism. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. 155-170

Urban, Neo-historical East Berlin, Architecture and Urban Design in the German Democratic Republic. 1970-1990, 246

Urban, F. (2009). Neo-historical East Berlin: Architecture and urban design in the German Democratic Republic 1970-1990. Farnham, England: Ashgate.